Yoni and Terry revisit the topics of Peirce's semiotics and Jewish PaRDeS (Peshat, Remez, Derash, Sod).

Yoni's SemioBytes blog posts are here.

Highly recommended reading:

Joseph Brent, Charles Sanders Peirce: A Life, revised edition, Foreword by Thomas A. Sebeok (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), paperback.

In a letter to his admirer and friend Chicago Judge Francis Russell in November 1904, Peirce wrote:

… whatever I amount to is due to two things, first, a perseverance like that of a wasp in a bottle & 2nd to the happy accident that I early hit upon a METHOD of thinking, which any intelligent person could master, and which I am so far from having exhausted it that I leave it about where I found it,— a great reservoir from which ideas of a certain kind might be drawn for many generations.

Peirce’s life story is an American tragedy and a disgraceful chapter in the history of academia. Brent’s biography began as his 1960 UCLA doctoral dissertation in history. Upon completion, however, it was relegated to obscurity by Harvard, who had acquired Peirce’s writing shortly after his death in 1914. They refused to allow publication of quotes Brent’s treatise contained from Peirce’s correspondence and other materials. The work languished in academic twilight until 1990, when Thomas Sebeok stumbled across an obscure reference to it, tracked it down, got in touch with Brent, and motivated him to revise, expand, and publish it. Its first edition appeared in 1993, and this 1998 enlarged and revised second edition stands as the definitive biography of America’s indisputably greatest philosopher.

Brent’s biography is a masterpiece for at least two reasons: his telling of the tragic tale of Peirce’s life is as brilliant and insightful as it is historically factual and detailed. His explications of Peirce’s astonishingly profound philosophy are as lucid and incisive as they are honest and inviting. No scholarly inquiry into the story of Peirce can be complete or cogent without plumbing the depths of Brent’s telling of it

As for “rehashing the basics” in our SemioBytes podblog episode of that title, while reading Brent’s biography I was blessed to discover that the most basic notion in Peirce’s philosophy is his fundamental trichotomy of categories. Anyone familiar with Immanuel Kant’s four triads of synthetic a priori categories as “pure concepts of the understanding” will have a sense of just what Peirce accomplished in distilling Kant’s dozen down to just three triads of categories (a total of nine) with no loss of metaphysical, phenomenological, transcendental, or logical power whatsoever. The three classes forming the triad are Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness. A simple illustration, borrowed from Brent (p. 333):

Mathematically and logically, triads cannot be reduced to dyads nor dyands to monads. But any more complicated thing can be reduced to a triad:

Peirce’s method involved using this categorical trichotomy as the “reservoir” from which to draw the triadic character of everything. As Brent explained, Peirce discovered this method in 1867 and it permeated his work thereafter.

Perhaps best known of all the triads Peirce generated from this fundamental one is the three kinds of signs: icons, indexes, and symbols. Each sign type manifests all three of those basic aspects of Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness. Icons, for example, are First as mere extant things, even if only possibly so — the monadic dot above is simply itself. Its Secondness lies in its dyadic relationship to the other dot based on similarity or likeness, proximity or alignment, etc. Its Thirdness emerges in its concurrent correlation with the other two. When we interpret the images as a bullethole, a buttonhole, and a billiard rack or equilateral triangle, say, we are semiotically giving those iconic, indexical, and symbolic categories their cognitive roles as objects, representations, and interpretations, respectively, in our own thinking. That is the essence of sign-processing, or semiosis.

Of course that is all a bit too arcane and abstract. Brent provides a more palpable and familiar illustration (p. 333):

The effort to understand Peirce on the categories sometimes gives one the giddy feeling of learning how to waltz—ONE, two, three; ONE, two, three; ONE, two, three…. The broken repetition of rhythm also resembles the mechanical gait of an insect (perhaps a wasp?). But, finally, the sheer beauty of the dancing categories evokes nothing so much as the chaotic and recursive fractal images of Benoit Mandelbrot plunging deeply into the microcosm and always reflecting lovely and minutely differing variations of themselves. There is also a close similarity to the dancing trinities of Christian and Hindu theology, a connection which Peirce recognized. For example, in the Christian Trinity, God the Father is Firstness, God the Son is Secondness, and God the Holy Ghost is Thirdness.

Brent chose Peirce’s self-description for the closing chapter of his book, “The Wasp in the Bottle.” As something or other of an itinerant philosopher in my own life from the inside of my own bottle, I resonate quite harmoniously with Brent’s observations (p. 335):

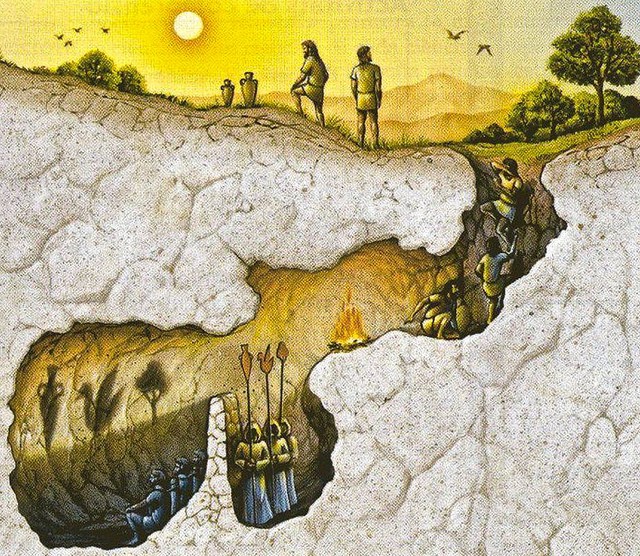

The image he created of himself as an angry wasp trapped in a bottle … seems wonderfully apt as a description of the Secondness of Peirce’s experience of life, but it also has broader meaning. The image clearly expresses the human condition: we are trapped behind a pane of metaphysical glass which we can see through darkly by means of the senses, but which distorts the reality see glancing beyond it. Peirce’s picture of himself as the furious wasp buzzing ominously but impotently about the cramped confines of his pellucid bottle, futilely jabbing at the slick glass with his stinger, pragmatism, in a lifelong attempt to penetrate the riddle and escape with the secret of the universe, only to die humiliated and unrewarded, seems to be no more than a metaphor for the unreasonable state in which we find ourselves.